In this article, we will delve deep into the realm of architecture project briefs, uncovering their purpose, components, and significance in shaping the built environment. Whether you’re a seasoned architect, a budding designer, or simply someone intrigued by the magic of architectural creation, understanding the intricacies of a project brief is your key to unlocking the secrets behind exceptional architectural design. So, let’s embark on this exploration together and unravel the mysteries of the architecture project brief.

Understanding the Architecture Brief: A Deep Dive

An architectural brief acts as the cornerstone of all design-led projects, encapsulating not only architecture but also elements of construction, communication, history, and theory. Whether you are an architect, a designer, or a student, at some point, you’ll encounter an architectural brief as it forms the basis of any design endeavor.

An architectural brief is essentially a comprehensive document centered around a specific design project. This document is meticulously prepared through a consultative process involving the project team and the client. The purpose of this process is to refine the client’s vision and expectations into a tangible and actionable framework that guides the design project.

The architectural brief is generally divided into two key parts:

- Project Brief or Scope of Services: This section elucidates the detailed requirements needed to deliver the project successfully. It includes processes and activities that the project team is expected to carry out, ultimately leading to the final physical outcome of the project. This can include:

- Project timeline or schedule;

- Budgetary limitations;

- Vital deliverables or benchmarks;

- Roles and responsibilities of involved parties.

- Design Brief or Scope of Works: This part outlines the physical parameters and expected results of the design or construction project. The design brief typically rests within the overall project brief and might cover areas like:

- Aesthetic or visual requirements;

- Functional or practical necessities;

- Materials to be utilized;

- Priorities regarding sustainability.

Architectural briefs can vary widely in size and complexity, ranging from a concise one-page document to a comprehensive multi-page guide, depending on the magnitude and intricacies of the project.

There are two standard procedures for creating an architectural brief:

- Pre-prepared Brief: In this scenario, the client or a consultant prepares the design brief, detailing the project requirements comprehensively. It is then submitted to an architect or designer during a tender process for them to present a fee proposal for project completion;

- Back-brief Approach: Here, the client provides preliminary information to the architect or designer, who then expands and refines the brief for greater detail. This work is usually compensated for until the final project and design brief is agreed upon, and the designer’s scope of services can be clearly stipulated.

Interestingly, universities often give students detailed architecture briefs or assign them to develop specific sections in more detail, providing practical learning experiences.

Now, let’s delve deeper into each of the project and design briefs to understand them more comprehensively.

Project Brief: The Scope of Services Uncovered

At the core of every design project lies the project brief or the scope of services. This is a detailed document that outlines the range of tasks and activities that the project team, including designers and consultants, are expected to accomplish to bring the project to fruition. The context and requirements of this document can vary between professional practice and academic settings. However, it’s beneficial to understand its relevance in both realms, as academic projects often mirror real-world scenarios.

Stakeholders: The individuals or groups who fund the project and make the final decisions are usually referred to as the client or sponsor. They play a crucial role in the direction of the project.

Project Timeline: Determining the schedule is a critical aspect of the project brief. It highlights the time allocated for the project along with major stages or phases for completion of work or services. In a professional setting, this timeline is usually determined by the client or negotiated with the lead architect or designer, depending on the project’s size and complexity. However, in an academic setting, this is typically a predefined time frame within a semester or a term. It’s crucial to understand this time frame for each project and manage it wisely.

Milestones: These are significant targets or goals set at regular intervals during the project duration to keep things on track and prevent delays. In a professional environment, milestones would include important deadlines such as town planning submission, tender process, contractor engagement, construction, and project completion. They could also encompass regular meetings with clients, consultants, or contractors at various stages of the project. Conversely, in an academic setting, these are generally week-to-week submissions, interim feedback sessions, and final presentations.

In academic settings, it can be beneficial to view your tutor or teacher as your client. This approach helps you understand their expectations and prepares you for professional practice. Consider what they expect of you as a professional designer or architect and consider the repercussions if you were to not complete any work between meetings. Handling academic projects in this way can significantly improve your project management skills, preparing you effectively for future professional engagements.

In summary, the project brief is much more than a list of tasks – it’s a roadmap that leads the way to a successful project outcome, ensuring that all parties involved are on the same page and working in harmony. Understanding and effectively using the project brief can greatly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of your design and architecture projects.

Decoding the Project Budget and Deliverables in a Project Brief

The Project Budget and Deliverables sections of the project brief play a pivotal role in shaping the project’s trajectory. These elements stipulate the financial and work boundaries within which the project must be confined.

Project Budget

The project budget is an integral component of the brief. It specifies the available funds for the entire project, encompassing the construction allowance, consultant and design fees, and miscellaneous costs, such as utilities and town planning fees.

In professional practices, the overall project budget typically is determined by the client or dedicated project manager. Design and consultant fees are frequently calculated as a proportion of this budget. The volume of the project and the estimated number of hours mandated to culminate the work often influence the final consultant fees.

In academic scenarios, students are not usually provided with a project budget as they aren’t paid for their work. However, an estimate of the expected hours to complete the project is generally provided. This timeline serves as a helpful gauge for managing time and work similar to real-world projects. Dividing the total project hours over the duration of the project provides an insight into the weekly workload. It is advisable to be prepared for scenarios when the work might take longer than anticipated.

Deliverables

The deliverables section of the project brief outlines the final work products, including the drawings, models, documents, and progress reports, that the team must create and submit. This section provides clear expectations of the tangible outputs expected from the project team.

In a professional environment, deliverables may encompass comprehensive document packages for concept presentations, town planning submissions, tender or construction packages, along with meeting minutes or interim reports. This detailed information facilitates clarity and ensures alignment among the stakeholders.

Academic project briefs usually require final and interim submissions, complimented by weekly work for feedback and review. It can also demand analyses and process work documentation. Treating these submissions with due importance and investing time in creating high-quality deliverables can significantly enhance learning and create a positive impression.

In conclusion, clear definitions of the project budget and deliverables in the project brief provide a concrete framework for managing project resources effectively. This approach can lead to greater efficiency, ensuring projects are completed within the allocated resources and timeline, and meet the expected quality standards.

Unpacking the Design Brief: Scope of Works Explained

The Scope of Works in a Design Brief is a comprehensive document detailing the physical attributes and expected outcomes of the building or construction project. The following sections delve into the core aspects of the Scope of Works:

Site Analysis

One of the initial steps in the design process is the analysis of the project’s location, its physical site boundaries, and the pre-existing conditions on the site. This evaluation covers:

- Site Location: Identifying the project site’s geographic location is crucial, as it provides essential information about the regional climate, architectural style, culture, and statutory regulations;

- Site Characteristics: Understanding physical elements like size, shape, topography, vegetation, soil type, and natural light and wind direction ensures an environmentally sensitive design approach;

- Existing Structures: Any pre-existing structures on the site and their conditions also need consideration. The information on these structures could impact the project feasibility, design scope and overall cost.

Typology

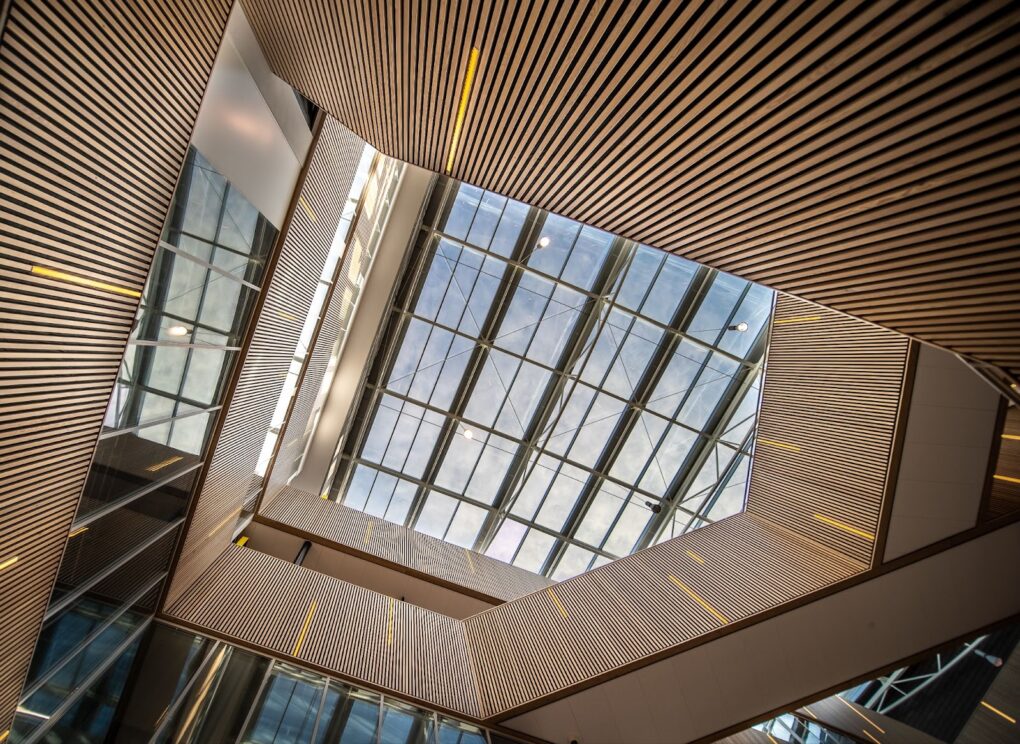

The ‘Typology’ section identifies the type of building or structure to be designed and built, whether it’s a residential house, an educational institution, medical facility, or a commercial space.

Key aspects to consider here include:

- Precedents: Studying established precedents or examples of similar buildings helps understand their essential features, aesthetics, and best practices. Real-world examples provide inspiration and guidance for new design projects;

- Standards and Guidelines: Knowledge of standard measurements and guidelines associated with specific building types is indispensable. For instance, hospitals have strict rules regarding spatial planning due to health and safety requirements.

User Profile

The ‘Users’ section identifies the people who will be using the final project or outcome. Understanding the users’ specific needs, habits, and lifestyles form the basis of a user-centric design approach. This information helps tailor spaces to their preferences and enhance the overall user experience.

Building/Structure Scope

This part offers a detailed description of the future project compared to the existing conditions. Information here includes:

- Type of Project: This section identifies if the scheme is a new build, refurbishment, renovation, or involves any demolition work;

- Estimated Size: Here, the overall size of the final structure and any associated works are articulated. This estimation serves as a helpful tool for spatial planning;

- Floor Levels: Information about the total number of levels, including both above-ground and basement, is included. This data impacts the building’s structural design and circulation planning.

The ‘Design Brief: Scope of Works’ is an instrumental guide that facilitates a systematic and efficient approach to achieving meaningful architectural outcomes. Understanding its intricacies and details helps architects and designers navigate through the various phases of the design process.

Delving into the Intricacies of a Design Brief

Architectural Program

The Architectural Program is a pivotal component of the Design Brief that provides a comprehensive breakdown of spaces and functions required in the project. This section is developed with careful consideration of the client’s requirements, users’ needs, and the functional parameters needed for the building to operate efficiently.

It consists of:

- Space List: A detailed list of spaces or rooms required in the building like classrooms in a school project or patient rooms in a hospital project;

- Spatial Relationships: An analysis of connections and adjacencies between rooms or functions can enhance the project’s functionality. For example, a kitchen should be near the dining area in a residential project;

- Space Allocation: Specifies the required size for each room or function, which aids in the creation of the preliminary floor plan.

Understanding and working within the stipulations of the architectural program is instrumental in making the design user-friendly and functional.

Materials and Techniques

Specific materials or construction technologies might need consideration depending on the building typology or location. For instance, a beach house might require corrosion-resistant materials because of its proximity to the sea. On the other hand, local regulations might stipulate the use of certain fire-resistant materials for an industrial building. This consideration feeds into the sustainability, aesthetics, budget, and even the construction timeframe of the project.

Assumptions, Constraints, and Opportunities

This section covers both tangible and intangible aspects that could affect the project:

- Assumptions: Statements taken as fact for the purpose of planning, even if they’re not yet confirmed;

- Constraints: Limitations or restrictions that could hinder the project, such as budgetary boundaries, regulatory constraints, or site conditions;

- Opportunities: Positive aspects that could be leveraged to enhance the project, like a favorable climate, unique site features, or advanced local construction techniques.

Vision, Goals, and Aspirations

Aimed at capturing the intangible and experiential aspects of the project, the Vision, Goals, and Aspirations section outlines what the client and end-users hope to achieve and experience from the final project. Here, more abstract concepts like the desired ‘feel’ of the space, the emotional response it should evoke, or the ‘story’ it should tell come into play.

In conclusion, each section of a design brief serves a unique purpose in the overall design process. It works as a flagbearer, guiding the project team towards creating a design that meets the physical requirements and offers an enriching experience to its users. By understanding and implementing these aspects, a designer or architect can ensure a successful and value-driven project outcome.

Mastering the Art of Reading and Utilizing a Project Brief

A project or design brief isn’t just another document in your academic or professional journey; it’s your roadmap to success. Whether you’re a student embarking on a university assignment or a seasoned professional taking on a new project, understanding and harnessing the power of a project brief is crucial. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve deep into the art of reading and using a project brief effectively to maximize your project’s potential.

1. The Crucial Role of a Project Brief

Your project brief is more than just a set of instructions; it’s a comprehensive guide that defines the scope, goals, and expectations of your project. Here’s why it matters:

- Clarity: A well-crafted brief provides crystal-clear directions, ensuring everyone involved understands the project’s purpose and objectives;

- Assessment Criteria: In the academic realm, the rubric or assessment criteria, along with the brief, illuminate precisely what you’ll be evaluated on. This includes various aspects such as process, design, development, presentation, and skill;

- Balanced Emphasis: The brief also highlights the importance placed on different facets of the project. Understanding this balance helps you allocate your efforts effectively.

2. Beyond Skimming: Making the Most of Your Brief

Don’t let your project brief become a mere paperweight on your desk or a digital file buried in your folders. Instead, treat it as your strategic companion:

- Print and Analyze: Opt for a hard copy of the brief whenever possible. This tangible format allows you to annotate and highlight key points, making it easier to reference during your project journey;

- Regular Revisits: Your project brief should never gather dust. Make a habit of revisiting it frequently to ensure you stay on track and meet all the requirements;

- Incorporate Feedback: As you progress, use the brief as a framework for soliciting feedback from peers, mentors, or clients. It will help you align your work with the stated goals.

3. Meeting Every Requirement with Precision

In both academic and professional settings, the responsibility falls on your shoulders to address every aspect of the project brief meticulously. Here’s how to do it:

- Break It Down: Divide the brief into manageable sections or tasks. Create a checklist to ensure you don’t miss any crucial elements;

- Allocate Resources: Assign resources, whether it’s time, materials, or team members, in alignment with the brief’s requirements;

- Constant Evaluation: Regularly assess your progress against the brief. If any deviations occur, address them promptly to stay on course.

4. Hard Copy vs. Digital Format: Choosing Your Weapon

While digital copies have their merits, opting for a hard copy can be a game-changer:

- Annotate Freely: With a hard copy, you can jot down notes, highlight essential points, and make personalized annotations that keep you organized and on track;

- Reduced Screen Time: Minimize eye strain and digital distractions by referring to a printed brief. It can enhance your focus and comprehension;

- Read about the art of crafting a visionary architecture program, shaping your creative dreams into reality with our expert insights.

Conclusion

In the world of architecture, the importance of a thorough and well-defined design brief cannot be overstated. It is the cornerstone upon which extraordinary buildings and spaces are built, enabling architects to transform ideas into tangible, functional, and aesthetically pleasing structures that fulfill the needs and aspirations of their clients and the communities they serve. Ultimately, the design brief is the catalyst that transforms architectural concepts into reality, shaping the built environment in ways that enhance our lives and our world.