In the realm of architecture, both academic and professional projects require a comprehensive site analysis. This process involves a detailed examination of the current and potential future conditions of a site. It delves into the physical attributes, patterns, activities, relationships, context, known facts, assumptions, opportunities, and constraints. This analysis encompasses both the immediate vicinity and the broader surroundings.

Steps in Conducting a Site Analysis

The process of site analysis in architecture is a meticulous and multi-staged endeavor that forms the backbone of any successful design project. It begins with the collection of existing data and documentation, an essential step that lays the groundwork for understanding the site’s current state and potential. This initial phase involves gathering a wide range of information, including historical records, previous studies, legal documents, and geographical data. These elements provide a comprehensive backdrop against which new observations and insights can be measured.

Following the desk-based research, an on-site visit becomes crucial. This step allows architects to immerse themselves in the physical environment of the site. Observing current conditions firsthand provides a reality check against the documented data. It’s during these visits that architects can appreciate the nuances of the site – its topography, the interplay of light and shadow, the flow of human and vehicular traffic, and the subtle ways in which the space interacts with its surroundings. This immersive experience often uncovers details that aren’t apparent in documents and maps.

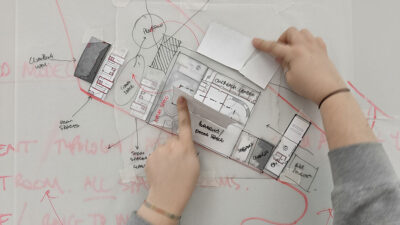

The subsequent analysis of the gathered data is where creativity intersects with practicality. Architects look for patterns, assess impacts, and identify opportunities. This analysis is not just about understanding what exists, but also envisioning what could be. It’s a process of synthesizing information to reveal new possibilities, identifying constraints that could become design challenges, and finding unique characteristics that could inspire innovative design solutions. The final step is the presentation of these findings. This stage is critical as it translates complex analysis into understandable and actionable insights. The presentation typically comprises a combination of documents, photographs, drawings, sketches, and other creative interpretations that articulate the site’s conditions. This comprehensive package serves not just as a record of findings but as a narrative that tells the story of the site – its past, present, and potential future. It becomes a tool for communication and collaboration, guiding the design process and informing decision-making from concept to completion.

Importance of Site Analysis

Conducting a site analysis early in a project is crucial for assessing feasibility and practicality, forming the foundation of the design process. A thorough analysis uncovers potential issues that might hinder the project or affect its outcome. These could range from physical constraints like easements or zoning restrictions to environmental factors like noise pollution or sunlight patterns. Understanding these elements helps in developing a design that maximizes opportunities and addresses challenges.

Categories of Data in Site Analysis

Three main data types are essential for a site analysis:

- Mega, Macro, Micro Data: This data ranges from the larger-scale environmental context to specific site details;

- Objective or Hard Data: Includes quantifiable and physical characteristics of the site;

- Subjective or Soft Data: Encompasses perceptions, feelings, and qualitative aspects of the site.

Each project may have unique elements, and not all aspects may be relevant in academic settings. Consulting with a tutor or teacher can provide clarity on the scope of analysis required.

The Role of Site Analysis in Design

A well-executed site analysis is a pivotal element in the architectural design process, serving as more than a preliminary assessment. It lays the groundwork for informed decision-making, ensuring that the design not only resonates with the site’s unique characteristics but also addresses the needs and expectations of its users. By comprehensively analyzing a site, architects can craft spaces that harmoniously blend with their surroundings, embodying both functional and aesthetic qualities. This thorough analysis involves a strategic examination of various data types across multiple scales, bringing to light a multifaceted understanding of the site. The process delves into the nuances of both objective and subjective data, each offering critical insights:

- Objective Data: This includes tangible, quantifiable information such as the geographical location, legal constraints, existing utilities, and infrastructural elements. It forms the factual basis upon which practical aspects of the design are built. Objective data ensures that the project adheres to legal standards, integrates smoothly with existing infrastructure, and aligns with the physical reality of the site;

- Subjective Data: These are the qualitative aspects shaped by human experiences and perceptions. This data encompasses how people interact with the space, the sensory experiences it offers, and the emotional responses it evokes. Subjective analysis is crucial in creating spaces that are not just physically accommodating but also emotionally resonant and contextually relevant;

- Three-Dimensional Scale Analysis: Site analysis extends across three distinct scales – Mega, Macro, and Micro. The Mega scale looks at the broader urban or regional context, understanding the site in relation to its wider environment. The Macro scale focuses on the immediate surroundings, considering adjacent buildings and local infrastructure. The Micro scale delves into the intricate details within the site, examining the fine-grained aspects that influence the user’s immediate experience.

By integrating these diverse layers of information, architects can create designs that are deeply rooted in the context of the site, responsive to its environmental, social, and cultural milieu. This holistic approach ensures that the final architectural product is not only a physical structure but a meaningful addition to its landscape, enhancing the quality of life for its users and contributing positively to its community.

Mega, Macro, Micro Scale Analysis

The Mega, Macro, and Micro levels of site analysis collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of a site’s context, each scale offering unique insights essential for thoughtful architectural design.

Mega Scale Analysis

At the Mega scale, the focus extends beyond the immediate boundaries of the site to encompass its broader context. This level considers the site within the larger framework of the suburb or city, examining how it interacts with and contributes to the wider urban landscape. Understanding the interconnections and dynamics at this scale is crucial for ensuring that the design aligns with broader urban planning objectives, respects the existing urban fabric, and contributes positively to the larger community. This analysis can reveal critical insights into regional trends, economic factors, and large-scale environmental considerations that shape the site’s potential and constraints.

Macro Scale Analysis

The Macro scale analysis is a critical component in the architectural site evaluation process, offering a lens through which the immediate context of a site is understood and interpreted. This level of analysis delves into the intricate relationship between the site and its neighboring environment. It involves a thorough examination of the surrounding buildings, street layouts, public spaces, and local infrastructure. This close examination is crucial in comprehending how the site interacts with its immediate context, both physically and functionally.

Understanding this interaction is key to making informed decisions about the site’s development. It sheds light on how the site can be accessed, the nature of its connectivity with adjacent areas, and the integration of new structures within the existing urban fabric. This scale of analysis plays a significant role in determining how a proposed design can complement and enhance the local streetscape and public realms.

Moreover, the Macro scale analysis aids in aligning the new development with the local aesthetic and functional norms. It ensures that the design not only respects but also contributes to the character and identity of the neighborhood. This level of scrutiny helps to avoid designs that are out of place or disruptive to the existing urban rhythm. By focusing on the Macro scale, architects can create spaces that are not just visually appealing but also add value to the community, fostering a sense of belonging and enhancing the overall quality of the urban environment.

Micro Scale Analysis

The Micro scale zooms in on the specific details within the site, focusing on the qualities and features of individual objects and elements. This granular approach is vital for understanding the site’s intrinsic characteristics, such as topography, vegetation, sunlight, and wind patterns. It also involves a close examination of the site’s sensory and experiential aspects, which are crucial for creating user-centric designs. The Micro scale analysis ensures that every aspect of the design is informed by and responsive to the site’s unique physical and experiential qualities.

Recognizing that a site does not exist in isolation but as part of an evolving ecosystem is key to successful architectural design. The site is intertwined with its surroundings, community, and the broader urban landscape, each influencing and being influenced by the other. By considering all three scales – Mega, Macro, and Micro – architects can ensure that their designs are not only aesthetically pleasing and functional but also deeply connected to the site’s unique context, contributing to the richness and diversity of the built environment.

Objective or Hard Data Assessment

Objective data are facts that remain constant, independent of human interaction. This includes:

- Location: Identifying the site’s geographic position, including address and lot number. Aerial photographs and maps help in understanding the site’s boundary, dimensions, and shape;

- Legal Aspects: Covering the site’s legal status, including ownership and access rights. This entails verifying the title, checking for any caveats, easements, or legal constraints;

- Authority Regulations: Assessing the site’s zoning, any applicable overlays (such as heritage or environmental), flood levels, and protected species. This step also includes understanding the local, state, and federal government regulations;

- Utilities and Infrastructure: Evaluating the site’s access to essential services like sewer, water, gas, electricity, and communications. This involves identifying the location and condition of these services;

- Adjacent Structures and Conditions: Examining land uses and conditions surrounding the site, including natural and artificial elements, their distances, heights, and styles;

- Streetscapes, Elevations, and Sections: Creating a comprehensive visual representation of the site’s vertical conditions, including panoramas and elevation details;

- Natural Physical Conditions: Analyzing the site’s topography, vegetation, geology, soil type, and animal species, along with any natural features or highlights;

- Artificial Physical Conditions: Investigating human-made features on the site, such as buildings, roads, footpaths, and street furniture;

- Climate Analysis: Studying the site’s climatic conditions across different seasons and times of the day, focusing on solar gain, shadows, precipitation, temperature, and wind patterns;

- Hazards and Risks: Identifying any potential risks, including exposed services, machinery, drainage issues, natural events, and derelict or unfinished buildings;

- Site History and Significance: Summarizing the site’s past uses and any contamination, archaeological, historical, cultural, and demographic significance;

- Neighbourhood Context: Considering the neighborhood’s history and its impact on the current condition, including significant buildings, architectural styles, and common materials used in the area.

Each of these aspects provides crucial insights into the site’s existing conditions and potential challenges, informing the architectural design and planning process.

Assessing Subjective or Soft Data in Site Analysis

Subjective or soft data in site analysis plays a pivotal role in shaping how a space is experienced and interacted with by people. These elements, dynamic and ever-changing, are deeply influenced by human presence and activity. They encompass the sensory experiences – sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch – which are crucial in understanding how individuals perceive and engage with a site. This type of data provides insights into the qualitative aspects of a space, offering a nuanced perspective that goes beyond the physical attributes.

Pathways and Movements

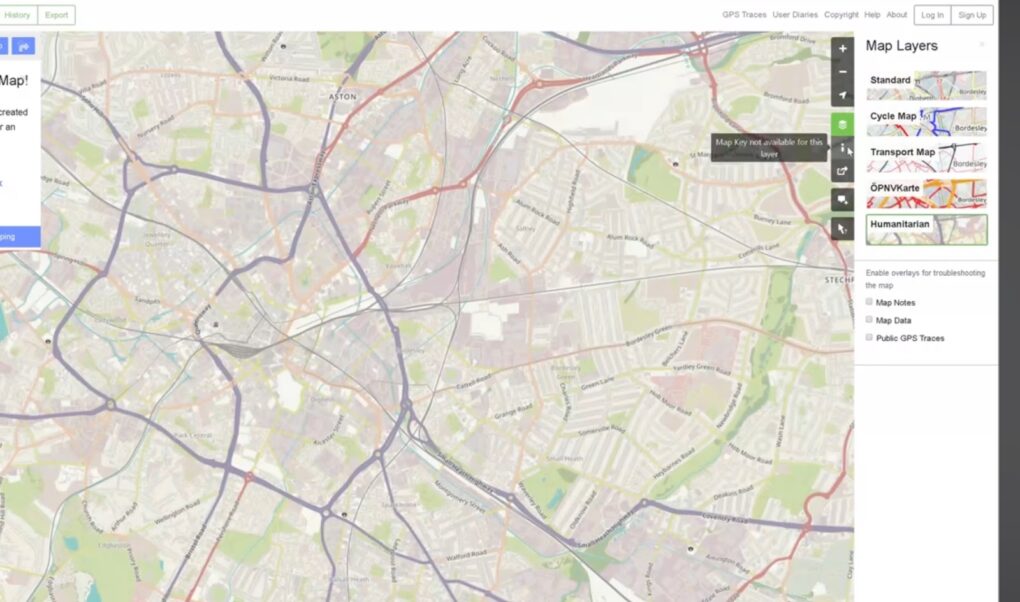

The “Access and Movement” component of site analysis is a critical factor in determining a site’s usability and appeal. This aspect delves into the intricate network of pathways that facilitate movement across the site, be it for pedestrians, vehicles, or animals. Understanding the interaction of these routes is key to creating a cohesive and efficient layout. It involves studying the entry and exit points, internal circulation paths, and their connections to broader transport networks.

The design and placement of these pathways have a profound impact on how the space is experienced. Well-planned routes contribute to the ease of navigation, enhance safety, and ensure seamless integration with the surrounding environment. They also play a significant role in defining the character of the space, influencing how people perceive and interact with it. For instance, pedestrian-friendly pathways can encourage foot traffic and foster a sense of community, while efficient vehicular routes can enhance accessibility and reduce congestion.

In essence, the analysis of access and movement is not just about the physical layout of paths but also about understanding their role in shaping the experience and functionality of the space. This understanding is essential in creating environments that are not only accessible but also inviting and harmonious with their intended use.

Visual Experiences

Views: Visual experiences play a crucial role in how a space is perceived. This involves analyzing the views both into and out of the site from various heights and vantage points. Understanding what can be seen from the site and what can be viewed from it helps in enhancing visual appeal and in considering the impact of the site on its surroundings.

Privacy Considerations

Privacy is a fundamental aspect in site analysis, playing a crucial role in shaping the user experience and functionality of a space. The assessment of privacy involves a meticulous evaluation of how private spaces within the site can be protected from external visibility and intrusion. This is not just a matter of physical barriers, but also a thoughtful consideration of sightlines, landscaping, and architectural design.

The challenge lies in striking a balance between ensuring privacy and maintaining openness and connectivity with the surrounding environment. This involves strategic placement of windows, walls, and fencing, as well as the use of natural elements like trees and shrubs to create natural barriers. Additionally, the orientation of buildings and internal spaces is carefully planned to minimize exposure to public view while maximizing natural light and views.

Ensuring privacy also extends to acoustic considerations, where the design seeks to shield internal spaces from external noise and prevent internal sounds from being heard outside. This aspect of privacy is especially crucial in residential and sensitive commercial areas, where tranquility and confidentiality are key. Incorporating privacy into the site analysis and subsequent design is essential for creating spaces where individuals feel secure and comfortable. This careful consideration enhances the quality of life for users and adds intrinsic value to the property, making it not only a functional space but also a personal sanctuary.

Safety and Security

Security, Protection, and Safety: This involves a thorough assessment of the site’s safety by examining both internal and external factors that could pose risks. It encompasses measures to protect the site and its occupants from external threats, and vice versa, ensuring a secure environment.

Sensory Impacts

- Sound and Noise: Identifying sources of noise both inside and outside the site is essential in determining how they affect the site’s ambiance. This analysis helps in creating a space that is acoustically comfortable and appealing;

- Smells: The analysis of smells involves identifying and understanding odors originating from within and outside the site. This includes assessing how these smells change with environmental factors and determining where protection or mitigation might be necessary.

Each of these aspects of subjective or soft data is crucial in creating spaces that are not just physically accommodating but also emotionally resonant and experientially rich. They contribute to making a site more than just a space – transforming it into an environment that people can connect with on a deeper level.

Desktop Analysis: The First Phase

The initial step in site analysis is desktop research. This stage involves gathering existing information and documents about the site and its surroundings. By conducting this research early, valuable insights can be gained into various aspects of the site:

In the complex and multi-layered process of architectural design, the meticulous gathering of site-specific data stands as a critical first step. Each aspect of the site analysis, from the location’s physical attributes to its legal and regulatory context, contributes significantly to the architect’s understanding and response to a given site.

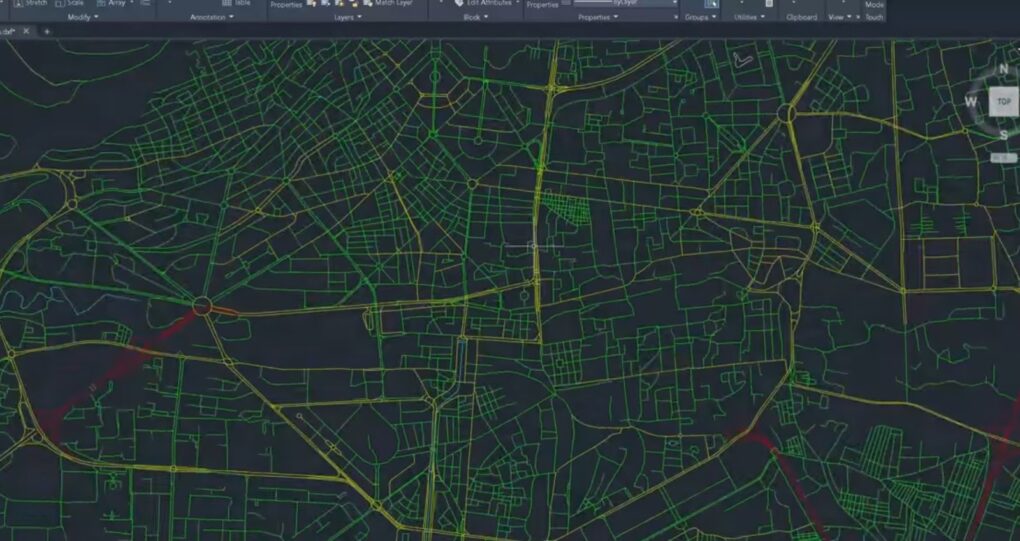

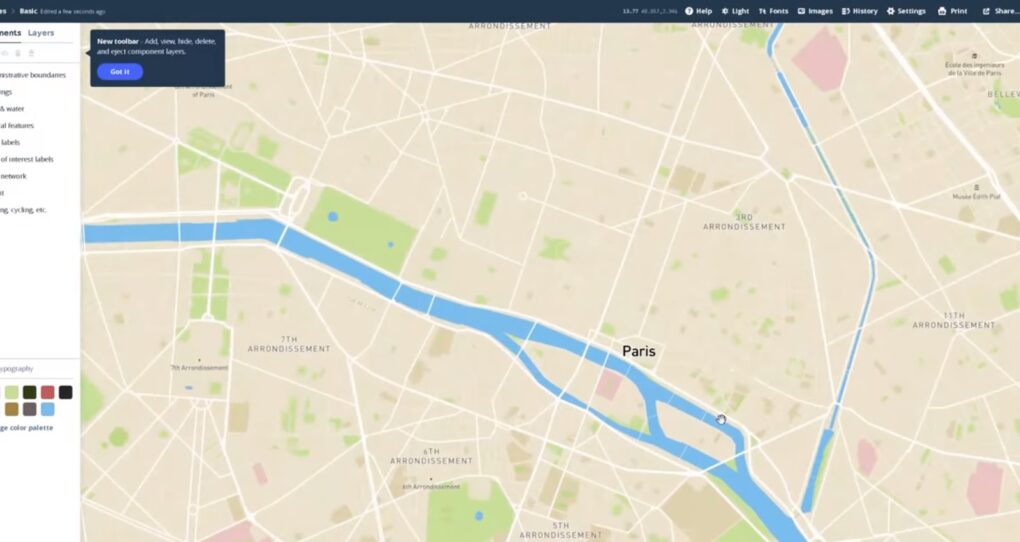

- Location: The collection of site surveys, aerial photographs, and maps is fundamental in establishing a clear understanding of the site’s physical context. These resources provide invaluable information about the site’s topography, existing structures, and natural features. They serve as a canvas upon which the architect can begin to envision the potential of the space;

- Legal Aspects: Delving into the legal intricacies of a site, such as titles, easements, and mortgages, reveals the boundaries within which the design must operate. Understanding these constraints is vital to ensuring that the proposed designs are feasible and legally compliant;

- Authority Regulations: Navigating through zoning documents, overlays, and development controls establishes the regulatory framework governing the site. This step ensures that the design adheres to local ordinances and planning guidelines, which can significantly influence the scope and nature of the project;

- Utilities and Infrastructure: Securing plans and drawings from service providers sheds light on the existing infrastructure network. This insight is crucial for integrating new designs seamlessly with existing systems and for planning future expansions or modifications;

- Adjacent Structures and Conditions: Researching neighboring structures and conditions helps in understanding the site’s immediate context. This includes assessing how neighboring buildings, land uses, and urban fabric might affect or be affected by the new development;

- Natural and Artificial Physical Features: Analyzing the site’s geology, soil conditions, and existing vegetation (through reports and surveys) informs decisions regarding foundations, landscaping, and environmental impact. This understanding aids in creating designs that are not only aesthetically pleasing but also sustainable and harmonious with the natural environment;

- Climate Analysis: Studying climatic factors such as sun paths, precipitation, temperature, and wind patterns is essential for creating comfortable and energy-efficient spaces. This analysis influences various design aspects, from the orientation of buildings to the selection of materials and the design of outdoor spaces;

- Site History and Significance: Investigating the site’s history and significance through photographs and reports provides a sense of the location’s past, informing a design approach that respects and reflects the site’s heritage and cultural context;

- Neighbourhood Context: Understanding the broader neighborhood through research provides insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of the area. This helps in designing spaces that are not only physically but also socially and culturally integrated into their surroundings.

Each of these steps, while distinct, interweaves to form a comprehensive understanding of the site. This thorough approach enables architects to design not just buildings, but meaningful spaces that resonate with their context, meet regulatory standards, and enhance the user experience. In doing so, architects transform sites into settings for life, interaction, and community, underpinning the profound impact of architecture on society and the environment. This comprehensive approach to gathering subjective data ensures a thorough understanding of how the site interacts with its human and environmental context, shaping the overall design and planning process.

Conducting a Site Visit for Architectural Analysis

After desktop research, a visit to the site is essential to confirm the gathered information and identify any discrepancies or new conditions. A successful site visit requires certain tools and preparations:

- Photographic Equipment: A camera or a smartphone with panoramic capabilities is vital for capturing various perspectives, both close-up and from afar;

- Clipboard and Documentation: Carrying a clipboard to hold a notebook and key documents (with annotations or post-its from preliminary research) helps in cross-checking facts on site;

- Notebook and Writing Tools: A notebook for jotting down observations and sketches, along with several pens and pencils;

- Measuring Tools: A tape measure or laser measurer to confirm or gather new dimensions;

- Carrying Gear: A backpack and clothing with large pockets keep hands free and tools accessible;

- Sustenance: Water and snacks are necessary, especially for extended site visits;

- Weather Consideration: Choosing a clear, sunny day enhances photo quality and visibility of colors, textures, and shadows.

Extended observation periods or multiple visits at different times may be required to fully understand the site’s dynamic conditions.

Gathering and Recording Data

The subsequent phase of site analysis, where data from desktop research and on-site observations are synthesized, is pivotal in transitioning from raw information to actionable insights. This phase is characterized by a series of detailed activities that collectively contribute to a deeper understanding of the site.

- Document Analysis: This involves a meticulous review of existing documents to distill key information. It’s about sifting through a wealth of data to identify the most relevant and impactful details. This process often results in a concise summary that captures the essence of the site’s historical, legal, and physical context. It’s a foundation upon which further, more nuanced analysis is built;

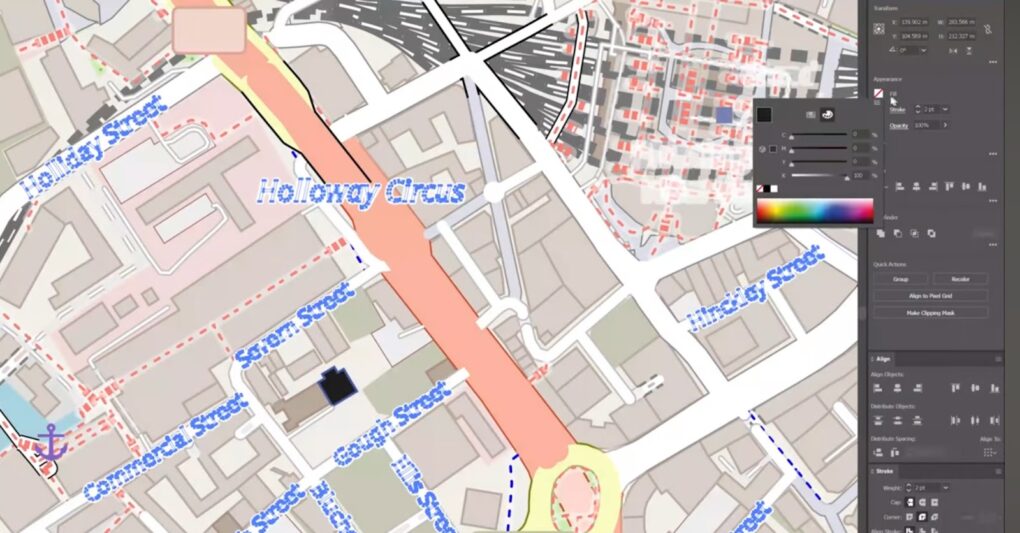

- Visual Analysis: Utilizing scale plans, maps, and photographs, architects overlay these with butter or tracing paper to conduct a diagrammatic analysis. This method allows for a comparative study of different layers of information, revealing patterns and relationships that are not immediately apparent. It’s a way of visualizing the interplay between various site elements and how they might influence future development;

- On-Site Records: The dynamic nature of a site is best captured through sketches, photographs, and annotated drawings. These on-site records are invaluable as they provide a real-time snapshot of the site, encompassing aspects like pedestrian flow, light conditions, and spatial dynamics. They offer a tangible link between theoretical data and the lived reality of the site;

- Developing Findings: This is where the analysis takes a creative turn. The gathered information is transformed into diagrams, annotated drawings, sketches, maps, or plans. This step is about interpreting data, turning observations into visual representations that articulate the site’s potential and limitations. These findings become a visual language that communicates the site’s story, setting the stage for design development.

Each of these activities plays a crucial role in building a comprehensive understanding of the site. Together, they form a bridge between raw data and creative architectural solutions, providing a robust platform for informed and innovative design decision-making.

Analyzing the Collected Data

With the data collected, the critical step is to interpret its implications for the design:

- Site Implications: Evaluating existing patterns, activities, relationships, and temporal changes on the site;

- Building or Structure Impact: Considering how the site affects the proposed structure’s massing, form, scale, access, views, light, and spatial relationships between private and public areas.

This stage is not just about data collection but also about understanding how these factors influence the final user experience and the design process. It involves integrating the site analysis with an understanding of the project brief, user needs, and preliminary concept ideas, highlighting the iterative nature of architectural design.

Structuring the Site Analysis Presentation

Presenting the findings of a site analysis, although not always compulsory, is a vital step in the architectural process, particularly when communicating with clients, authorities, or academic supervisors. The manner in which these findings are presented can greatly influence how the information is perceived and understood. The format of this presentation can vary significantly, ranging from a straightforward site plan to a comprehensive and detailed report. The key is to choose a format that best suits the audience and the purpose of the presentation.

For instance, when presenting to clients, the focus might be on visual representations and summaries that clearly illustrate how the site’s characteristics will influence the proposed design. In contrast, a presentation to regulatory authorities might require a more detailed report, emphasizing compliance with zoning laws and regulations.

The structure of the presentation is equally important. It should be organized in a way that logically and effectively highlights the most pertinent information. Starting with an introduction that sets the context, the presentation can then progress through the various levels of analysis – from broad overviews to specific details. Including visuals such as maps, photographs, and diagrams can make the data more accessible and engaging, especially for those who may not be well-versed in architectural terminology. Ultimately, the goal of the site analysis presentation is to convey the depth and breadth of the research conducted, showcasing the thorough understanding of the site and its context. This not only demonstrates professionalism but also builds confidence among stakeholders in the viability and thoughtfulness of the proposed design.

Crafting the Introduction

Start with an overview, providing a snapshot of the site and the key findings.

Detailed Sections of the Report:

- Location (Mega and Macro): Incorporate location plans at various scales, utilizing aerial photographs to depict the existing site;

- Legal and Authorities: Offer a concise summary or references to any pertinent legal and authority requirements;

- Site History and Significance: Summarize the research findings about the site’s past and its importance;

- Neighbourhood Context: Detail the research findings, supplemented with photographs and sketches;

- Existing Conditions Photographs: Present key photographs of the site, referencing each image’s location;

- Streetscapes, Elevations, and Sections (To Scale): Include essential drawings to showcase vertical information and context;

- Site Analysis Plans: Display observations and findings of both objective and subjective data. These could be consolidated into one or several diagrams, illustrating patterns, activities, conditions, opportunities, and constraints. Each diagram should be clearly labeled with a legend or key and simple annotations if needed;

- Sun Path and Shadow Diagrams: A straightforward layout of diagrams representing different times of day and year, each labeled with a legend or key.

The Role of Site Analysis in the Design Process

Site analysis stands as the inaugural chapter in the narrative of architectural design, setting the tone and direction for the entire project. This initial phase, far from being a mere formality, is crucial to the project’s ultimate success. A comprehensive site analysis lays a robust foundation, rich in insights and information, from which the design can organically evolve. It’s akin to an artist first understanding their canvas – knowing its textures, strengths, and limitations before beginning to paint.

By thoroughly examining the site, architects can draw upon a deep well of inspiration. The unique characteristics of the site – its topography, history, cultural context, and environmental aspects – become the catalysts for creative thinking. This process of discovery and understanding informs the development of design concepts, ensuring they are not only innovative but also contextually relevant and responsive.

Moreover, a detailed site analysis guides critical design decisions throughout the project. It helps in identifying potential challenges and opportunities, allowing architects to strategize and plan effectively. Decisions regarding the building’s orientation, spatial layout, material selection, and environmental sustainability are all deeply influenced by the initial site analysis. In essence, site analysis is not just a preliminary step but a continual reference point throughout the design journey. It ensures that the resulting architecture is not only aesthetically pleasing but also deeply rooted in its specific place and context, thereby enhancing its relevance, functionality, and longevity.

Exploring and Engaging with the Analysis

Add 200 words “Approach site analysis not merely as a task to be completed but as an opportunity for exploration and excitement. Continually question the implications of each finding on the design. Use the checklist to determine which aspects are most critical for each site and project. Assess which elements require deep investigation and which may need less attention. Focus your resources on the aspects that will most significantly influence your design, for better or worse. This approach ensures a more thoughtful, informed, and impactful design process.

Conclusion: Harnessing the Power of Comprehensive Site Analysis

In conclusion, the process of conducting a thorough site analysis is not just a preliminary step but a cornerstone in the architectural design journey. It offers more than just a collection of data; it provides a deep understanding of the site’s context, history, and potential. By meticulously gathering and analyzing both objective and subjective data, architects can uncover hidden opportunities, foresee potential challenges, and tailor their designs to resonate with the site’s unique characteristics.

A well-structured site analysis presentation acts as a bridge between raw data and creative architectural solutions. It facilitates clear communication with clients, authorities, and team members, ensuring that all stakeholders have a shared understanding of the site’s nuances. This shared understanding is crucial for developing design proposals that are not only aesthetically pleasing but also contextually appropriate and sustainable.

Furthermore, the site analysis process encourages architects to adopt a curious and investigative approach. It’s an exercise in critical thinking and creativity, prompting questions about how each element of the site – from its sun paths to its socio-cultural fabric – will influence the final design. This holistic understanding fosters designs that are more than just structures; they become meaningful spaces that enhance their environment and serve their users effectively. In essence, the site analysis is a foundational element that shapes the trajectory of the entire architectural project. It’s an indispensable tool that empowers architects to craft designs that are not only visually stunning but also deeply rooted in the context and narrative of the site. This rigorous and thoughtful approach ultimately leads to architectural creations that stand the test of time, both functionally and aesthetically.